The flowers, the branches

the birds

of my frosty window

are fading away

dawn

is breaking its way

and through

myriads of magnifying tears

Seoul appears

Seoul the monster

Seoul the dirty

the unfriendly

Seoul

Seoul my new City

A Sun

shy and cautious

-- has it been hurt too --

is now hanging

purple and blue

curtains

at my window

silence in

silence out!

A sparrow,

the morning and I

tremble

at the sudden

full throated cry

of a cock

a cock alive in Seoul

in 1993 Seoul

A new day

coming from nowhere

is sailing in

a day full of gold and silver

magic fruits and pastels

a brand new day

is entering Seoul

Seoul my new born City

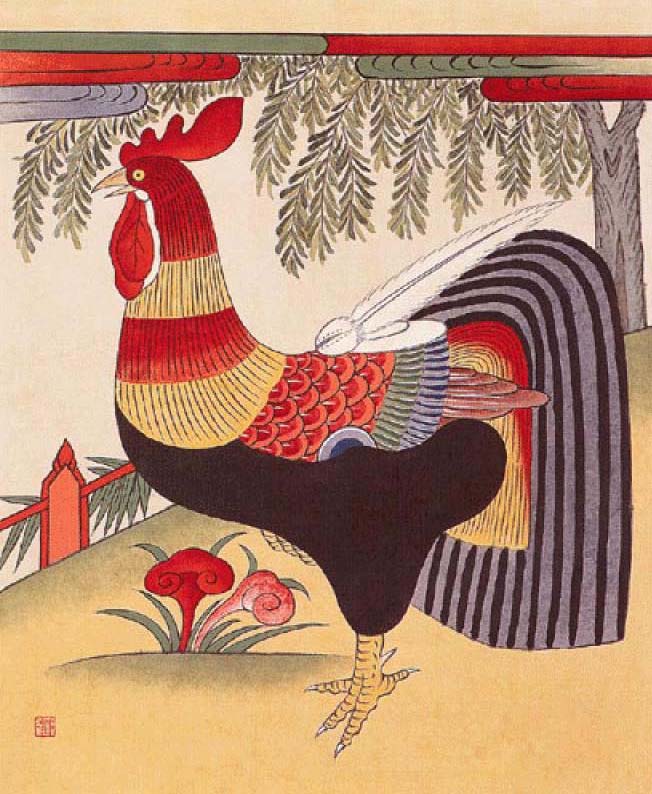

Roosters have long been a popular subject in Korean folk art. They were regarded as auspicious symbols of fertility, wealth, fame, and a successful career, and represented five virtues: intelligence, strength, courage, heartedness (sincerity, earnestness), and trust. They guided newly-dead souls into the afterlife.

ReplyDeleteIt is no wonder that in this poem the rooster resonate for Paulette, since "le coq gaulois" is an unofficial national symbol of her homeland, France. The Roman historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus noted that the Latin words for rooster and Gaul were homonyms ("Gallus"), but there was no "Gallic nation," only a loose confederation of Gallic tribes, and they had no sacred roosters in their mythology that could be the basis for national self-identification. Moreover, though the cock was a sacred animal among some Celtic Gauls, who associated it with their analog for Mercury, the Irish deity Lugh "samhildánach" ("Equally skilled in many arts") and his Welsh counterpart Lleu Llaw Gyffes ("The Bright One with the Strong Hand"), this connection was true only for British Gauls, not French ones. The rooster's specific association with France dates back only to the Middle Ages, when France's enemies used the same Gallus/gallus wordplay to ridicule the French. The barb's sting was made sharper because of the ridiculous figure cut by the cock Chanticleer in popular French tales that appeared from the mid-12th century onwards: through guile and flattery, the fox Renard manages to use the rooster's own loud, proud, cocky, and gullible nature against him (although Chanticleer manages to save himself by similarly using Reynard's traits against him). During the Renaissance, the French kings, seeking to bolster their nation's position as a Catholic state, claimed their nation began with the 496 baptism of Clovis I, "the first Christian king of France," and embraced the association with the roster as a powerful Christian symbol (the rooster crowing during Jesus' arrest caused Peter to recall Jesus' prediction that he would deny Jesus three times before the rooster crowed; the crowing at dawn symbolizes the daily victory of light over darkness; it is an an emblem of watchfulness and readiness for the sudden return of Jesus, the resurrection of the dead, and the final judgment of mankind).

The popularity of that association faded, only to be recast by the anticlercal, antiroyalist leaders of the French Revolution, who discarded the Clovis myth as the origin of France and traced it back to Gaul and revived its connection to the rooster, colloquially referred to as "Chanteclair." It has been a national emblem ever since, especially during the Third Republic, when it was featured on 20-franc gold coins from 1899 to 1914. After World War I it was depicted on countless war memorials. It is often used as a national mascot, particularly in sports such as football (soccer) and rugby. The 1998 FIFA World Cup, hosted by France, adopted a rooster as its mascot. Le Coq Sportif ("The athletic rooster") makes sports equipment and uses a stylized rooster and the French tricolour flag as its logo. Pathé, the French film producer and distributor also has a rooster logo. The Walloon Movement ("wallingantisme"), an umbrella term for all Belgian political movements that either assert the existence of a separate Walloon identity or defend French culture and language within Belgium, typically regards the rival Flemings as the successors of the Dutch, Austrian, and Spanish occupiers of "Wallonia," the predominantly French-speaking region of Belgium, which comprises 55% of its territory and a third of its population. In 1913, the Walloon Movement adopted "le coq hardi" (the bold rooster) with raised claws, rather than the "singing rooster" that is traditionally depicted in France, as its symbol, and in 1991 it was officially adopted as the symbol of the French Community of Belgium, the political entity responsible for matters related to culture and education. (The German-speaking minority in the east forms the German-speaking Community of Belgium, which has its own government and parliament for culture-related issues.) In 1998 Wallonia also adopted the Wallon rooster image. In both France and in Wallonia, the onomatopeiac sound of the rooster crowing, "Cocorico," is used to express national pride.

ReplyDelete